Market research and human psychology predict if you should invest in this season’s hottest piece of PPE

I know what you’re thinking.

“Should I invest in the hottest new AI-powered face mask startup from San Diego?”

Personally, I’m throwing in all my life’s savings —$37.28 and a Tim Horton’s gift card (I don’t actually know the balance). Face masks have become essential in the fight against Covid-19 and brands are getting creative with new and sexy FASHION masks:

But is there any longevity to this product? Some Asian cultures like China and Japan already wear face masks as a part of their daily outfit, but could that trend translate to Western markets after this scare is over? Are fashionable face masks, sold anywhere from H&M to Louis Vuitton, going to be the next big thing in face apparel?

Well, there are a few ways to approach these questions:

- “Take it at face value”— (Market analysis)

- “The reviews are great!” — (Cultural neuroscience)

- “Probability, my dear Watson” — (Networks and informational cascades)

At face value, it’s got mask market appeal…

(Get it?)

Let’s think about profitability — how much money can a face mask really make after the pandemic?

Stringking’s made-in-America masks are selling at a little over $6 per mask in bulk, so we can assume outsourced cloth face mask production will be half of that, maybe even less after the pandemic.

Quarantine Fact: Normal surgical masks used to cost about 14 cents.

If wholesale prices fall anywhere between $3–6, we can apply the Keystone principle — a 50% markup. If we assume the wholesale price for an H&M mask is $4.50, we double it to $9.

Face masks have the potential to ride the post-apocalyptic streetwear culture wave, so we might see $10–15 masks at other fast-fashion joints.

Luxury masks: LVMH had gross margins of about 65% in 2008, and some claim their handbags have markups of 90%. Let’s estimate a 75% markup on Louis Vuitton face masks. Assuming a slightly higher wholesale price at $6, we apply the following formula used to determine selling price:

Selling price = [(cost of item) ÷ (100 — markup percentage)] × 100

Plugging in our values, we get:

Selling price = [($6) ÷ (100–75)] × 100

Selling price = $24

Realistically, a Louis Vuitton face mask would be made of leather, not cloth — I’d like to give you an approximate figure for a leather face mask, but Googling it left me deeply disturbed.

- Market size: People love to spend money on their faces — the global cosmetics industry is set to reach $430 billion by 2022.

- Competition: Scattered with no brand value. The fastest-moving players can fill the vacuum.

- Recurring revenue: Successful curated subscription box services like Dollar Shave Club and Ipsy pave the way for face mask subscriptions like MaskClub.com.

Strong demand, high markups, a growing market, and recurring revenue? From a numerical perspective, high-fashion face masks seem to hold some business potential.

Unless you get beaten out by these absolutely gangster bandana masks the CDC is teaching you how to make at home:

But numbers never tell the whole story — they’re sneaky like that. Luckily, the brain is very revealing…

Other_people_42 rated this mask: ⭐⭐⭐⭐

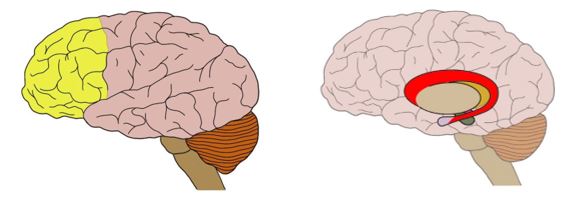

And your medial prefrontal cortex + caudate nucleus agree

We like popular people, and for good reason. If other people like them, they must be pretty well adapted for survival, right? Doing and liking what’s popular has an evolutionary advantage — it explains why hipsters were so quickly adapted out of the population.

Social influence is when the behaviours, beliefs, and preferences of other people influence our own. A study by Mason, Dyer, and Norton (2009) aimed to find a neurological basis for how this happens.

They used 30 random symbols in the experiment throughout 2 phases: 10 tagged as popular, 10 tagged as unpopular, and 10 new symbols that participants wouldn’t see until the second phase.

When participants saw symbols that were tagged (the ones they saw in the first phase) vs. new, untagged symbols (they didn’t know other peoples’ opinions of these) there was greater activation in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).

The mPFC is associated with thinking about other people’s attitudes and preferences; it’s active when we have social information about what we’re viewing/thinking about, regardless of whether it’s popular or unpopular.

They saw greater activation in the caudate when participants saw popular symbols vs. unpopular ones. The caudate nucleus is associated with the reward pathways in your brain.

Your brain rewards you for being part of what’s popular because it usually has an evolutionary advantage. Humans are a social species - adopting group behaviour builds a stronger connection with your group, which helps you survive.

Not to mention, if everyone in your tribe is frantically running in one direction, it’s probably for a good reason - there’s wisdom and safety in crowds.

The mPFC activates when seeing something we know people have an opinion about, and the caudate fires when that something is popular.

This is the neurological underpinning of whether something like a brand or clothing item (like a fashionable face mask) becomes popular—but how can we determine the likelihood of this happening?

Well, according to my calculations…

It depends on the number of people.

Information cascades occur when people make decisions sequentially, even if it goes against their own private information, based on the observed decisions of other people.

Let’s assume we have a group of people (N) who can decide between adopting and rejecting the fashion face mask trend. Everyone can observe the decisions of people in front of them, but not their private information (explained later).

We can build a mathematical model for what decisions they’ll make, based on the following components:

States of the world: The world randomly exists in either of two states, one where wearing face masks for fashion is a good idea (G) and one where it’s a bad idea (B)—individuals will try to figure which one is true.

Signals: Everyone has private information, or a private signal, that gives them a clue about whether accepting is a good idea or not—maybe in this case, it’s your existing knowledge of fashion.

Signals can be high (H), meaning accepting is a good idea, or low (L) meaning it’s a bad idea. If it is, in fact, a good idea, then high signals will be more frequent than low ones.

Mathematically speaking, the probability of getting a high signal given it’s a good idea (denoted by Pr [H |G], or q) will be greater than 0.5. Pr [L | G] will therefore be 1 – q. The same applies for the opposite:

As a rule, the first person will follow their signal, as will the second. (Proof can be found here).

- If Person 1 and 2 make different decisions, person 3 is indifferent and will follow his own signal.

- If they make the same decision (accept or reject the trend) person 3 will follow suit regardless of their private information.

This speaks to a trend that governs information cascades:

- If the number of acceptances exceeds rejections by two, it starts a cascade of acceptance.

- If the number of rejections exceeds acceptances by two, it starts a cascade of rejection.

This means three matching signals in a row will always cause a cascade. Let’s split N up into chunks of 3 consecutive people: the probability that they all get the same signal is:

q3 + (1 − q)3, or q × q × q + (1 − q) × (1 − q) × (1 − q).

By the same reasoning, the probability none of them get identical signals (i.e. no cascade happens) is

(1 − q3 − (1 − q)3)N/3.

As N approaches infinity, this value starts to = 0.

That mean the more people there are in the sequence, the likelier a cascade is to form. This could be a cascade of acceptance or rejection—if you want the former, encourage the first few people to all accept, and the rest will follow suit.

TL;DR — Will face masks be the next big thing in fashion?

- From a market analytics standpoint, they may have some potential for standard retail margins, but nothing crazy.

- If a group is wearing face masks, that social influence will activate the medial prefrontal cortex and caudate nucleus in the brain to reward you for fitting in.

- Mathematically speaking, if you can get 3 people in a sequence to adopt face masks as a fashion trend in a big enough population, it’ll spread virally (pardon that slightly inappropriate pun).

Why does this matter to me?

- Don’t Google leather face masks trying to find a production price—I mean it

- If you’re trying to build an army to do your bidding, activate their mPFC and caudate into thinking serving you is the socially acceptable course of action.

- If you’re trying to start a trend, just get two other friends to join you and you’re set. (Use this power for good).